Animal trials were a serious and common practice in medieval Europe, far from being an oddity. They served a solemn legal purpose, reinforcing societal control and notions of property rights through the prosecution of animals accused of crimes.

The charges varied widely but shared an element of surreal absurdity. Here are ten of the most notorious cases, listed by the species on trial, in ascending order of peculiarity:

1. Dogs

Dogs held a distinct status from livestock in medieval times—they were considered akin to people. Similar to women and serfs, they were even included in the weregild, a compensation paid to their owners by those who harmed them. In Old Germanic law, dogs, along with cats and roosters, could serve as witnesses in court. For example, if a dog was the only witness to a burglary at its owner’s house, the homeowner could bring the dog to court along with three straws from the roof thatch to symbolize the crime scene.

However, engaging in sexual acts with dogs was condemned by Christian sensibilities. In fact, historical records show that a Parisian man was once burned alive for “coition with a Jewess,” with the court equating it to the severity of having intercourse with a dog (the woman was also burned alive). Another notable case occurred in 1606 in Chartres, where a man convicted of sodomizing a dog was sentenced to hang. He managed to escape before the execution, leading authorities to hang a portrait of him instead of carrying out the sentence.

Despite such severe penalties, not all cases involving dogs ended in death. In 1712, for instance, a drummer’s dog that bit a councilor in the leg was spared execution. Instead, it was sentenced to one year of imprisonment in the Narrenkötterlein, an iron cage placed over the marketplace.

2. Termites

When the Portuguese invaded Brazil, they brought their peculiarities with them, leading to a bizarre incident where Franciscan friars accused termites of vandalism. These friars, followers of a man who preached compassion towards animals centuries earlier, were disgruntled by the termites consuming their food and damaging their furniture.

In an unexpected turn, the defense lawyer, resembling Saint Francis in spirit, argued passionately for the termites’ right to sustenance, likening their industriousness favorably to the idle friars. He emphasized that the termites had inhabited the land long before the friars arrived.

After a lengthy trial that concluded in January 1713, a compromise was reached: the friars agreed to set up a reservation where the termites could live undisturbed. This decision was communicated to the termite mounds, and remarkably, the termites were said to have emerged in columns and moved peacefully to the designated area. This act was interpreted as a sign of their submission to divine authority.

Thus, this unusual trial between Franciscan friars and termites became a testament to the complexities and peculiarities of human interactions with the natural world during the colonial era.

3. Monkeys

During the Napoleonic Wars, when some Englishmen discovered a monkey on a beach, suspicion immediately arose. The monkey had washed ashore near the wreckage of a French ship, the sole survivor looking bedraggled and miserable. Unfamiliar with actual Frenchmen and influenced by propagandist caricatures depicting them with claws and tails, the Englishmen mistook the monkey, dressed in a sailor’s attire as the French ship’s mascot, for a human spy.

In a swift and informal trial held right on the beach, the monkey was convicted of espionage and sentenced to death. It was hanged from the mast of a fishing boat—a stark example of extrajudicial mob law, a practice that, while frowned upon, was not uncommon for punishing animals in that era.

Interestingly, an alternative theory suggests that the creature hanged may not have been a monkey at all, but rather a child serving as a “powder monkey,” tasked with priming cannons with gunpowder. Regardless of the true identity, the incident has left a lasting legacy in Hartlepool, where locals are affectionately referred to as “monkey hangers.” Embracing this peculiar history, the town’s football team even adopted a monkey named H’Angus as their mascot. In a playful nod to their heritage, a mayoral candidate dressed as H’Angus in 2002, promising free bananas for school children, and successfully won the election.

4. Weevils

After devastating some vineyards in a French hamlet, weevils found themselves in a legal quandary. Represented by a capable lawyer, their trial concluded in the spring of 1546 with a surprising verdict: the judge ordered the locals to seek forgiveness from God, recognizing that He created the earth for all creatures. The hamlet also organized three solemn processions with prayers and songs around the vineyards. Remarkably, the weevils seemed to retreat—for a while.

Forty years later, the weevils returned, prompting another trial. This time, the case was brought before the prince-bishop of Maurienne and his vicar-general, meticulously recorded over 29 folios with a lengthy Latin title. The proceedings dragged on for months. The defense argued that blaming the weevils for God’s wrath was unjust, asserting the insects had a natural right to feed on plants. They ridiculed the idea of applying human laws to creatures as “absurd and unreasonable.”

In contrast, the local vine-growers, acting as plaintiffs, insisted that weevils should be subject to human control. The case was repeatedly adjourned as both sides presented their arguments. Eventually, the weevils’ legal team contended that even if subject to human authority, punishment such as excommunication was unwarranted—reserved solely for God. Two and a half months later, a verdict was reached: the people were ordered to allocate a piece of land fenced off for the weevils to reside peacefully.

However, the arrangement failed to prevent further conflicts. Within a month, the case was reopened as the vine-growers petitioned the judge to enforce the weevils’ confinement under threat of excommunication. Meanwhile, the defense argued the allocated land was insufficient and lacked adequate food for the insects. The trial faced multiple delays before a final verdict was eventually anticipated. Unfortunately, the last page of the court records, containing the verdict, was reportedly devoured by weevils, leaving the outcome forever shrouded in mystery.

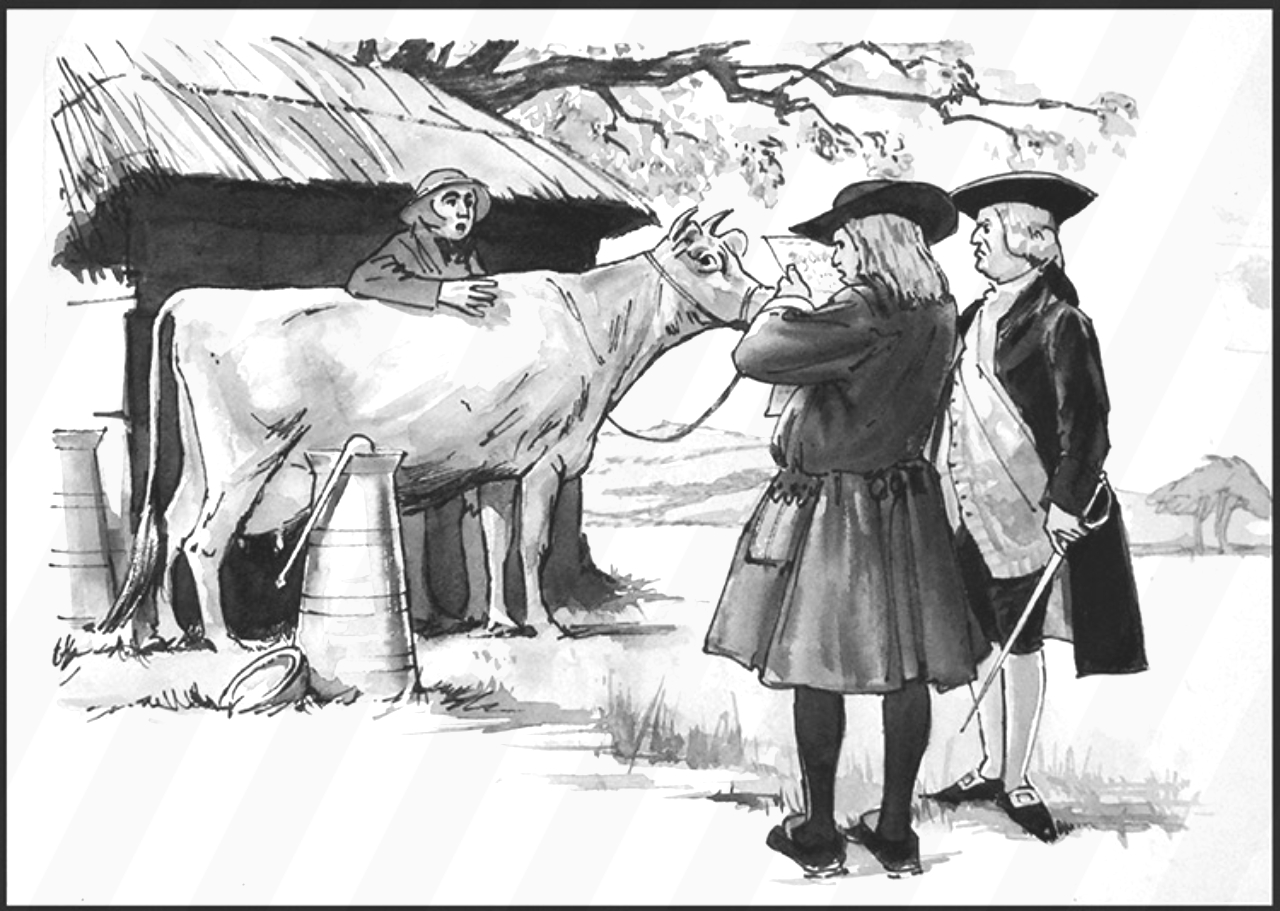

5. Cows

Due to their size, weight, and occasional aggression, cows often faced charges for deadly attacks. In 1314, for example, a bull broke free from a farm in France and fatally gored a man. Subsequently, it was captured by the Count of Valois’s men, imprisoned, and sentenced to hanging. However, since the Count lacked jurisdiction in Moisy, the sentence was overturned—albeit too late, as the bull had already been killed.

There are several other documented cases of lethal cows being sentenced to hang. Nevertheless, due to their economic value, cows and bulls, much like horses, were typically confiscated instead. In 12th-century Burgundy, a law stipulated that if an ox or horse caused one or more deaths, it would not be executed but taken by the feudal lord of the jurisdiction where the incident occurred, who would sell it and keep the proceeds. The law humorously added that “if other beasts or Jews do it,” they would be hanged by their hind feet.

Traditionally, animals sentenced to death—even organic, grass-fed cows from the pre-industrial era—were not consumed as meat. It was believed that eating such animals, which had been elevated to the same level of criminal guilt and punishment as humans, would amount to cannibalism, hence they were usually buried alongside human criminals. However, there were exceptions. For instance, in 1578 in Ghent, Belgium, a cow involved in a deadly incident had its flesh sold to a butcher to compensate the victim, while its head was displayed on a pike near the gallows.

6. Rats

As recently as the 19th century, rats were dealt with in a peculiar legal manner. They were served what was called a “writ of ejectment” or a “letter of advice” aimed at persuading them to vacate houses. To ensure the rats noticed these notices, they were often rubbed in grease to attract their attention. A notable example from Maine expressed sympathy for the rodents, urging them to leave 1 Seaview Street for 6 Incubator Street, where they could find ample food such as vegetables in a cellar or grain in a barn. The letter sternly warned that if the rats did not comply, they would face extermination by poison.

Going back further to the 1500s, rats faced even stranger legal proceedings. In Autun, a French province, rats were summoned to court for devouring all the barley crops. Aware that the rodents would not appear in court, the judge planned to punish them in absentia. However, the defense lawyer for the rats argued that a single summons was insufficient given the large rat population in Autun—it was impossible for all rats to be aware of the summons. Reluctantly, the judge ordered a second summons to be proclaimed from all parish pulpits throughout the province. Despite this, when the rats still did not appear, their lawyer argued that the journey was too perilous due to the presence of cats along the route, granting them the “right of appeal” and allowing them to refuse obedience to the summons.

7. Donkeys

Like humans, animals were also entitled to appeals in medieval legal proceedings. For instance, one donkey that was initially sentenced to hang had its fate altered when an appeal to a higher court resulted in a commutation of the sentence to a mere knock on the head.

Appeals sometimes even led to full acquittals. In a notable case from 1750, a donkey accused of seducing her rapist was acquitted after the parish priest of Vanvres provided a certificate affirming her impeccable character. The certificate, signed by the priest and other respected parishioners, testified that the donkey was “most honest in word and deed, and in all her habits of life.”

However, not all animals received such leniency. In 1565, a mule that had been raped by a man was sentenced to burn at Montpellier. Adding to the severity of the sentence, the court records noted that the mule was deemed “vicious and inclined to kick” (vitiosus et calcitrosus). The executioner, taking matters into his own hands, went further by cutting off its feet before burning it—a drastic and extrajudicial mutilation that likely earned him reprimand from the authorities. Courts generally disapproved of such actions by executioners, emphasizing the importance of adhering strictly to the legal sentence.

8. Caterpillars

In 1659, five Italian communes filed a complaint against caterpillars for wreaking havoc on their crops. Summonses were posted on trees in the forests, but unsurprisingly, the caterpillars did not show up in court. Nonetheless, the court conceded that caterpillars, like humans, possessed the right to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” as long as their pursuit did not infringe upon human interests.

In another curious legal episode involving insects, even bees found themselves in court. In 864, the Council of Worms (referring to the city in the Rhineland, not the species) sentenced a hive to be suffocated as punishment for causing the death of a human through stinging. The execution was to be carried out swiftly to prevent the hive from producing any honey, which was considered “demoniacally tainted” and unfit for Christian consumption due to the “murderous” act.

9. Slugs

In 1487, the slugs of Autun faced a peculiar situation: after devastating crops, they were given a generous warning through three days of public processions. During these events, they were officially ordered to vacate the area “under penalty of being accursed.” Similarly, the following year in Beaujeu, slugs were warned three times that failure to leave the province would result in excommunication. Despite the absurdity of warning slugs of excommunication, the ecclesiastical courts used this measure to legally sanction their extermination.

Even snails faced prosecution in France on multiple occasions: in 1487, 1500, 1543, and 1596. However, historical records do not reveal the specific punishments they received.