In a 2017 study by the American Psychological Association, it was found that the average museum visitor spends about 27 seconds observing a painting considered a masterpiece, with a median of 17 seconds. This might suggest a decline in attention spans due to social media and mobile devices, although it’s only slightly less than a similar study from 2001.

Considering this, it’s understandable how even with millions viewing them over years or centuries, subtle surprises, embellishments, or even humor can go unnoticed in plain sight. Some of these discoveries add a delightful twist, while others completely change how we interpret the artwork. Join us as we explore 10 timeless masterpieces and uncover their hidden secrets and meanings.

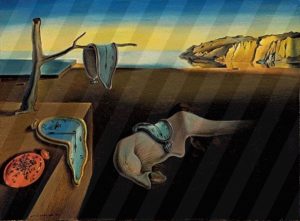

1. Persistence of Memory

For those with a casual interest in art, Salvador Dalí’s 1931 self-portrait might be the only painting they recognize. Known famously for his melting clocks, one might wonder if this iconic work depicts Dalí reflected in one of those surreal faces, or if the clocks symbolize aspects of his identity.

In fact, Dalí’s self-portrait in this painting is not what one might expect. He is represented by an object resembling a crumpled pelt on the ground, with his elongated nose extending along the bottom edge. His eye is closed, and notably absent is his trademark mustache, which would become a prominent feature later in his public persona, famously appearing on the cover of Time magazine in 1936.

The unconventional depiction of his face, with its unique angle and form, may have eluded many viewers over the years, given the painting’s minimalistic composition. However, now that this interpretation is highlighted, it’s likely to be a detail that cannot be unseen by those revisiting the artwork.

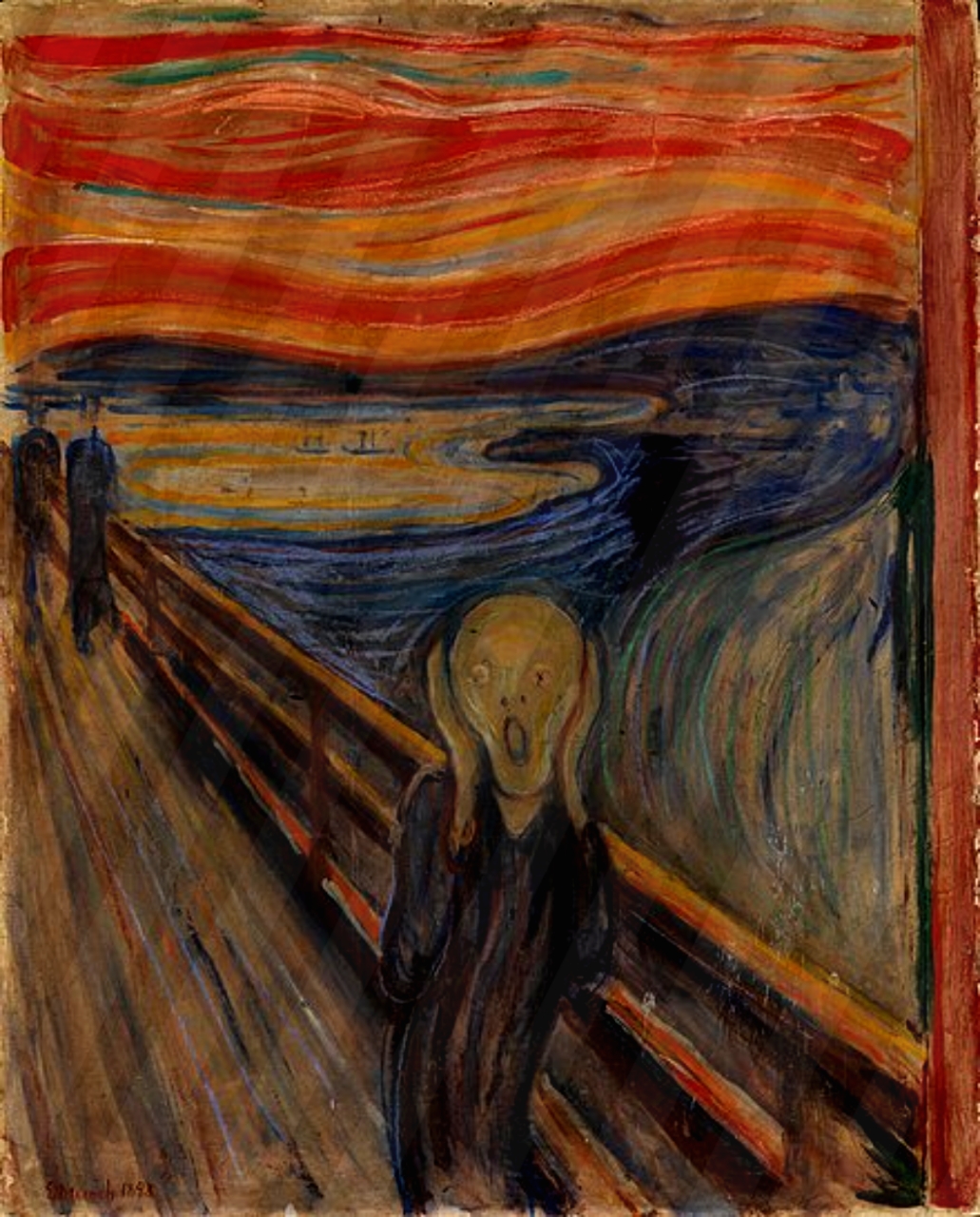

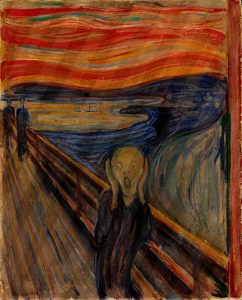

2. The Scream

Edvard Munch, renowned for his 1893 masterpiece inspired by a panic attack triggered by a vivid sunset, often had the finer aspects of his work overlooked. In 1895, the words “can only have been painted by a madman” were found scrawled in the upper left corner of the painting. Initially, it was believed to be the act of a displeased viewer responding to the critical reception of the painting. However, it wasn’t until 2021 that it was revealed Munch himself had penned those words out of frustration.

Historical records placed Munch in Oslo at the time of the incident. He had taken offense to Johan Scharffenberg, a psychology student, who implied that Munch might be mentally unstable. This perceived diagnosis hurt Munch deeply, prompting him to inscribe his own work with the provocative statement as a reaction akin to receiving a harsh critique.

3. Sistine Fresco

Past TopTenz lists have delved into Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ordeal, portraying it not as a labor of passion or triumph but as a grueling task. Even in his supposed cameo, a portrait of the skinned Saint Bartholomew, Michelangelo’s dissatisfaction with the project and his patrons was evident. However, this wasn’t the extent of his displeasure.

According to ABC News, when Michelangelo was coerced by Pope Julius II to return and expand the chapel, he embedded a subtle critique in his paintings. In “The Last Judgment” section, he depicted a putti (often mistaken as a cherub) making a gesture known as “the fig” towards the Prophet Zacharias, whose face was modeled after Julius II’s. Additionally, the depiction of the opening to Perdition was strategically placed near where the pope would sit. Surprisingly, this dissatisfaction didn’t hinder Michelangelo’s future commissions from the Catholic Church, suggesting either his critique went unnoticed or Pope Julius II, despite his nickname “Il Papa Terribile,” took it in stride.

4. Old Man in Military Costume

In the era of today’s global supply chains and abundance, it’s easy to overlook the significant material shortages that once impacted the art world. Even during one of the more prosperous periods of his career, Rembrandt faced such constraints and had to reuse entire canvases.

In 1968, during a comprehensive study involving x-raying all feasible Rembrandt paintings, researchers made a startling discovery about his work from 1630-1631 (exact dating varies). Initially interpreted as a tribute to Dutch resilience against Spanish adversaries, the canvas was found to conceal an earlier image of a fresh-faced young man. However, the x-ray technology of the time provided a murky view.

In 2015, the Los Angeles Times reported a breakthrough using new Macro X-ray Fluorescence technology. This revealed detailed information, including the revelation that Rembrandt had turned the canvas upside down before repurposing it—a practice akin to 17th-century recycling.

As of now, it remains unclear whether the Getty Museum, which owns the canvas, plans to market this artwork as a unique two-for-one deal.

5. Mural

Jackson Pollock’s splatter art has become not only his artistic legacy but also a subject of fascination and intrigue. Despite revelations later in his life, such as the CIA’s support of his popularity and his tragic death in a drunk driving accident, his abstract works remain prominently featured in the art world. One of his pivotal pieces, “Mural,” unveiled in 1943, has been reconsidered in a surprising light.

In 2009, the wife of art historian Henry Adams made a remarkable discovery: amidst what appeared to be chaotic layers of paint, she discerned a rough, cursive approximation of Pollock’s own signature. This revelation challenged the conventional view of “Mural” as mere splashes of paint, suggesting it was a deliberate and symbolic statement by Pollock himself.

The scale and unconventional nature of Pollock’s signature raise intriguing questions about his artistic intentions and what other hidden messages or meanings might lie concealed within his other works. This discovery invites us to rethink Pollock’s artistry and its deeper, potentially overlooked dimensions.

6. Earthly Delights

Hieronymus Bosch, a pioneering Dutch artist of the 15th century, fused naturalistic style with surreal subject matter. While many of his surviving 35 paintings and eight drawings focus on religious themes, it is his fantastical depictions of hybrid creatures and bizarre scenes in triptychs like “The Temptation of Saint Anthony” and “The Last Judgment” that often define his work. Among the myriad oddities, such as birds with floppy ears delivering mail and ears with knives, there’s a peculiar detail in “The Garden of Earthly Delights” that often goes unnoticed.

At the bottom of a figure partially obscured by cloth, Bosch painted what turned out to be actual, playable music for a demonic character. This discovery was made when a musician named Amelia, posting on Tumblr, transcribed and recorded a rendition of the music. With both the musical notes and a hypothetical performer depicted, Bosch’s work stands as perhaps the only Renaissance painting to feature a piece with a verifiable soundtrack. Curiously, it is humorously referred to as “butt music” due to its unconventional origin.

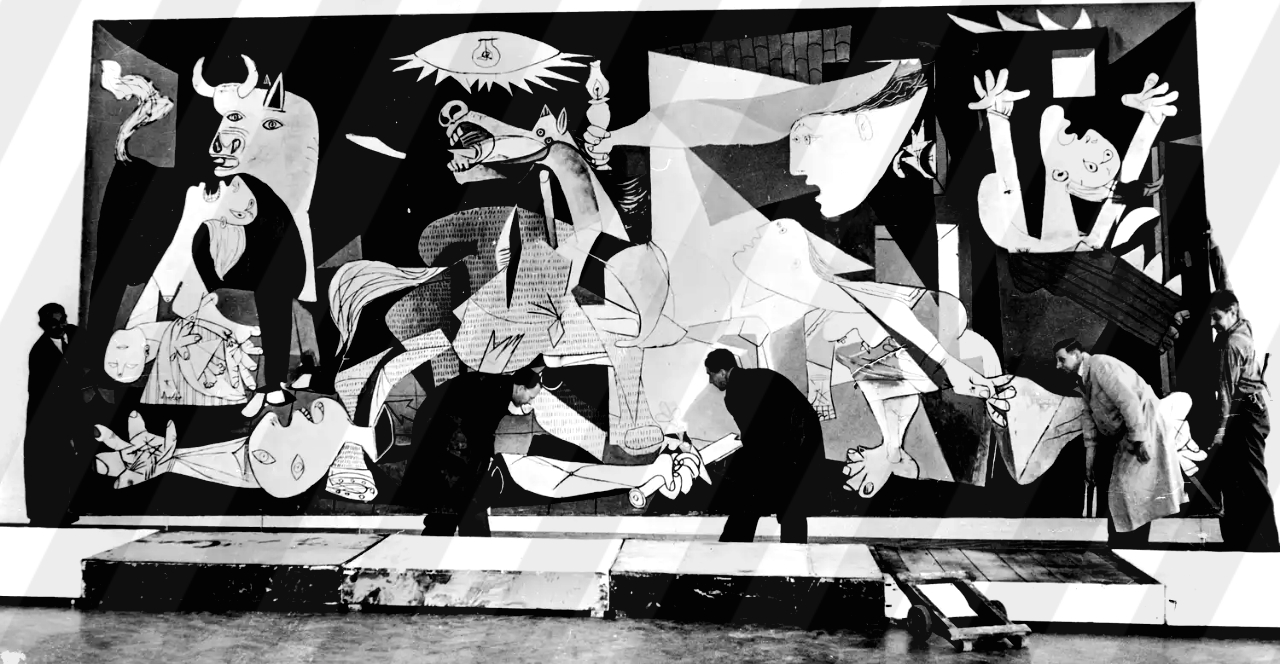

7. Guernica

Pablo Picasso’s monumental 1937 artwork depicting the aerial bombardment of Guernica, a stark condemnation of Francisco Franco’s fascist regime and the rising threat of the Third Reich, is renowned for its intricate symbolism. Despite its vast size, approximately 11.5 feet by 25.5 feet, the painting conceals symbols that took decades for experts to decipher, often stirring controversy.

One particularly enigmatic figure in the composition is a cubist representation of a woman in profile, both eyes placed on one side of her head, holding a kerosene lantern. This figure, it has been revealed, symbolizes the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). The key clue is a five-pointed object beside her head, resembling a combination of the Soviet star and the hammer and sickle, iconic symbols of Soviet communism.

The USSR’s support for the Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War was not merely symbolic; it was substantial and strategic. The Soviets provided crucial military aid, including nearly 1,500 aircraft and 900 tanks, among other weapons. This support was motivated by geopolitical considerations, especially in light of Adolf Hitler’s expansionist ambitions outlined in Mein Kampf, which targeted the Soviet Union for Lebensraum.

Picasso himself was a staunch advocate of the Soviet Union, communism in general, and its leader Stalin, despite later revelations and criticisms, such as Nikita Khrushchev’s denunciation in 1956. His art not only reflected his political convictions but also served as a powerful testament to the complex alliances and conflicts of his time.

8. Supper at Emmaus

Caravaggio, renowned for his provocative paintings of intense biblical scenes during the 16th and 17th centuries, was not only an artist but also a figure known for his tumultuous life. His clashes with the law included an incident where he threw rocks at guards, shielded by his papal connections until his eventual flight from Rome in 1605 after killing a pimp during a brawl that originated from a tennis match. Four years earlier, Caravaggio subtly inserted what appears to be a nod to the clandestine existence of early Christianity.

In the biblical tale depicted in his painting “Supper at Emmaus,” Jesus Christ meets with the apostle Luke and his uncle Cleopas after his resurrection, only to vanish afterward. Caravaggio’s rendition of this scene includes a wicker fruit basket prominently placed in the foreground. As noted by the BBC, the partially undone weave of the basket forms an Ichthys, a fish-shaped symbol used secretly among Christians in the 2nd century AD when the religion was persecuted in the Roman Empire. Adding to the intrigue, the shadow cast by the fruit basket resembles more the tail and dorsal fin of a fish than a mere heap of fruit.

While it might seem redundant to embed a Christian symbol within an explicitly Christian painting, columnist Kelly Grovier suggests that Caravaggio’s intention was to underscore themes of recognizing divine presence. The oblivious innkeeper in the painting serves to illustrate this point: while he remains unaware of Christ’s significance, those who recognize him are deeply moved.

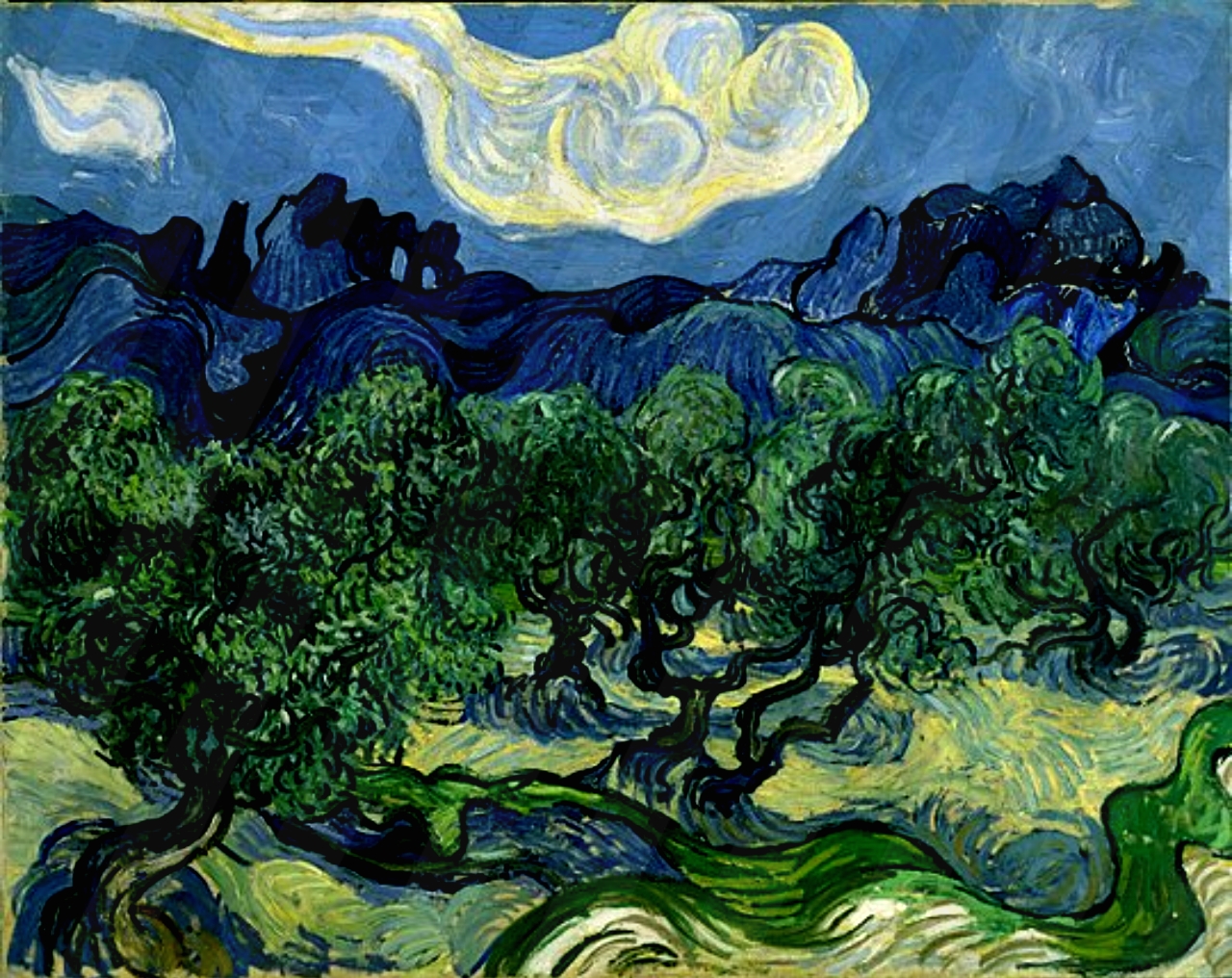

9. Olive Trees

Completed by Vincent van Gogh in September 1889 during his time as a patient in an asylum, The Olive Trees is part of a series of paintings depicting the groves he frequented during his permitted outings from the institution. What remained unnoticed until 2017 was a fascinating detail that turned the artwork into an accidental mixed-media piece. Conservator Mary Schafer, examining the painting with a magnifier, discovered the impression of a grasshopper leg embedded in the canvas. Additionally, she identified traces of a blade of grass and other debris, evidence of van Gogh’s practice of painting outdoors. This discovery would not have surprised Vincent himself, who once wrote to his brother Theo about the numerous flies he had to remove from his paintings: “I must have picked off a good hundred flies.”

David Lynch, renowned primarily for his filmmaking but also a prolific painter, shares a similar appreciation for accidental elements in art. According to David Hughes’s The Complete Lynch, Lynch’s advocacy for the creative value of accidents in art stems from an incident where an insect flew into one of his wet canvases, unintentionally smudging the paint in a way that intrigued him. Lynch’s embrace of these unexpected occurrences contrasts with van Gogh’s likely frustration with the disruptions caused by insects during his painting sessions.

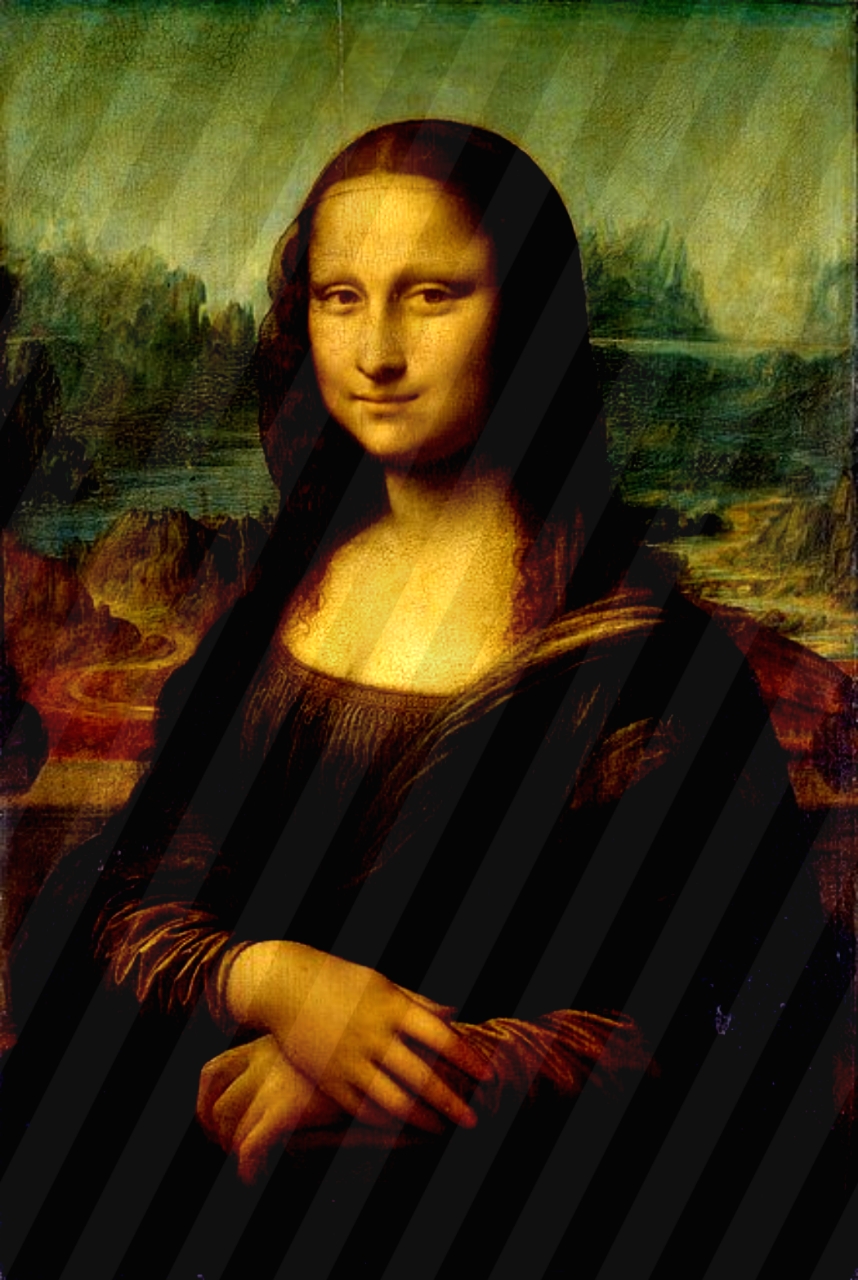

10. Mona Lisa

Painted between 1503 and 1519, Leonardo da Vinci’s portrait, commonly believed to depict Lisa Gheradini, became the most famous painting in the world under less than dignified circumstances. Initially stolen in 1911, the Mona Lisa gained further notoriety in 1919 when Marcel Duchamp created a defaced parody of its postcard version. These incidents underscore how easily overlooked are the symbols hidden in plain sight.

In the right pupil of the Mona Lisa, Leonardo subtly painted the letters LV, while the left pupil bears the letters CE. In the background, he inscribed “149” with a partially erased fourth digit, suggesting the painting’s creation a decade earlier than conventionally believed. Ironically, researcher Silvano Vinceti, who highlighted these details in 2010, credited another art historian’s 1960s book for leading him to this discovery.

Dustin Koski co-authored the post-apocalyptic supernatural comedy “Return of the Living,” a work teeming with secrets that invite multiple readings to uncover them all.